Jacob and Yerba are best friends. When they met three years ago, Yerba was immediately drawn to Jacob. Jacob knew it, too, when Yerba rolled on her back and licked his face.

As I’m sure you’ve guessed, Yerba and Jacob are no ordinary couple. Jacob is a 14-year-old boy living with autism and cerebral palsy and Yerba is a yellow Labrador retriever carefully bred and trained to help Jacob navigate the life that is often so scary and confusing for him.

CCI skilled companion dog Yerba licks Jacob’s ear as they snuggle with Jacob’s mom, Candice, at home.

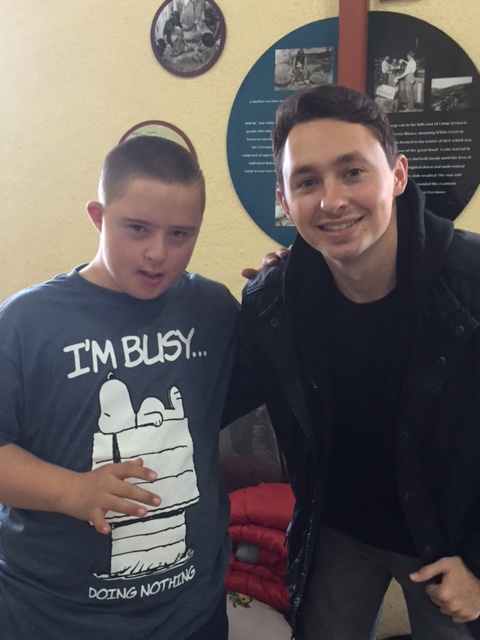

Their story began in 2012 when Jacob and his mother, Candice, went to a local park. There they met a young girl with Down syndrome and autism who had a “skilled companion” dog provided free by Canine Companions for Independence (CCI).

After researching CCI, Candice applied for a dog for Jacob, hoping it would help him with his anxiety and other social challenges. Nearly two years later, Jacob and Yerba met and their friendship has made an amazing difference for Jacob.

“He’s gained so much independence since he got her,” says Candice. “She knows her role and can sense when he needs her.”

Navigating life together

Jacob transitioned from elementary to middle school just a few weeks after he got Yerba. Stressful for even the most socially skilled 11-year-old, the move was scary and intimidating for Jacob. With Yerba at his side he was able to integrate much more easily. “After the first week, the other kids knew Jacob and Yerba by name,” says Candice, noting that people are curious about Yerba, who wears a special vest. Jacob has learned to answer strangers’ questions about her, building his confidence.

That extra attention can, however, be too much for him at times. Candice recalled a reunion with the person who raised Yerba as a puppy. The gathering with multiple dogs drew a crowd, and Jacob immediately became anxious and withdrew. Yerba sensed his anxiety and instinctively went to him, calming him and shielding him from the crowd.

She also recalled how helpful Yerba was when Jacob was hospitalized for pneumonia. Jacob’s grandmother brought Yerba along to the hospital when she visited him, keeping him calm so he could use his energy to heal. “He sits next to Yerba and puts his hand on her. It really calms him,” says Candice.

Yerba is always there for Jacob, even when he must be hospitalized for pneumonia.

Power to help

I was introduced to the CCI way by Sharon Mosbaugh, a volunteer “breeder caretaker” in Danville, CA. Sharon takes care of Salinas, a female breeder dog, and tends her litters. Sharon introduced me to Salinas and her litter of five pups, just days old. Sharon cares for them for their first eight weeks, when they are sent to volunteer “puppy raisers” who provide care and socialization and teach them basic obedience skills for the next 16-18 months.

I got to hold one of the tiny pups and couldn’t understand how Sharon could care for litter after litter and then let them all go. “How can I not give them up?” she asked. “When you see the power they have to help others, it’s really magical.”

At 18-20 months, the young dogs are sent to one of six regional training centers across the U.S. where they receive extensive training to serve in one of four specialized roles:

- Service dogs, who assist adults with disabilities by performing daily tasks

- Hearing dogs, who alert their partners, who are deaf or hard of hearing, to important sounds

- Facility dogs, who work with clients with special needs at places such as schools, court houses, and hospitals, and

- Skilled companions, like Yerba, who enhance independence for children and adults with physical, cognitive, and developmental disabilities

CCI breeder dog Salinas quietly nurses her pups just days after they were born in the home of breeder caretaker Sharon Mosbaugh.

Science and service meet at CCI

Sharon explained that breeder dogs, like Salinas, are the best of the best in terms of temperament and other traits required to provide the services clients require. All breeding occurs within 90 miles of CCI headquarters in Santa Rosa, CA, to maintain the control and consistency so important to the process.

Since its beginnings in 1975, CCI has placed more than 5,000 dogs across the U.S. Many more have been born into the program, but not all are cut out for the work ahead. “They won’t send a dog out to work unless they are absolutely certain of what it will do,” says Sharon.

She says that CCI is closely involved in every stage of the dog’s life to be certain it receives quality care and provides quality service. When a dog is retired, CCI places it with a loving owner and the client may apply for another dog.

CCI’s scientific approach attracts premier researchers who team with CCI to learn about the traits that make CCI dogs special. The organization is working with a consortium of canine research centers from Emory University, Georgia Tech, the University of California at Berkeley, and Dog Star Technologies on a study focused on the reward center of the canine brain.

A CCI pup learns the basics with a puppy raiser before moving on to specialized training. (CCI photo)

The dogs just know

One of the most special traits of the CCI dogs is their sense for who needs help. “I’ve watched it work,” says Sharon, who worked with service dogs as a school administrator in Indiana and California.

She told the story of a young student in Indiana who was traumatized by the death of a teacher and a family member in a short span of time. He refused to return to school. When his parents finally got him to the campus, he refused to go in.

Sharon met him at the car with the school’s facility dog, Sally. The dog went to the boy and put her paw on his arm. He soon calmed down and agreed to take Sally for a walk around campus. He decided to stay.

“People have no idea how profoundly the dog will change their lives,” she says. “They were my secret teaching weapon.”

Get a dog or get involved

The CCI website is loaded with great information for people interested in getting a dog or volunteering in some capacity.

If you think you might be interested in a dog, check out this helpful page to determine if a service dog is right for you. CCI receives more applications than it has dogs available, so only the people who will benefit most will be considered.

CCI can’t do what it does without a large team of dedicated volunteers. If you would like to volunteer or help CCI in other ways, here are some ideas.

If you do get involved, I’d love to hear and share your stories of how these amazing dogs are changing lives.

needs. I created this blog to tell stories of exceptional people, including those with special needs and those who give of themselves to make life better for them. My hope is that these stories expose more people to what’s good in the special needs world and inspire them to give of themselves to make life better for those with special needs.

needs. I created this blog to tell stories of exceptional people, including those with special needs and those who give of themselves to make life better for them. My hope is that these stories expose more people to what’s good in the special needs world and inspire them to give of themselves to make life better for those with special needs.

The Wanderer

The Wanderer

About me: I am Pete Resler, a dad of two boys with special needs. I created this blog to tell stories of exceptional people, including those with special needs and those who give of themselves to make life better for them. My hope is that these stories expose more people to what’s good in the special needs world and inspire them to give of themselves to make life better for those with special needs.

About me: I am Pete Resler, a dad of two boys with special needs. I created this blog to tell stories of exceptional people, including those with special needs and those who give of themselves to make life better for them. My hope is that these stories expose more people to what’s good in the special needs world and inspire them to give of themselves to make life better for those with special needs.

blog to tell stories of incredibly good people, including those with special needs and those who give of themselves to make life better for them. My hope is that these stories expose more people to what’s good in the special needs world and inspire them to give of themselves to make life better for those with special needs.

blog to tell stories of incredibly good people, including those with special needs and those who give of themselves to make life better for them. My hope is that these stories expose more people to what’s good in the special needs world and inspire them to give of themselves to make life better for those with special needs.